Phineas Gage was a young man seriously injured in a work-related accident. So what makes him so significant in psychology? His brain injury was shocking and the result impact on his personality quickly became one of the most famous case studies in psychology and neuroscience.

Phineas Gage: A Closer Look

On September 13, 1848, a 25-year-old railroad foreman named Phineas Gage was injured in a horrific accident. While using an iron rod to tamp explosive powder into a hole, the powder ignited and sent the 43-inch long rod hurtling upward. The rod pierced through Gage’s cheek, passing though the frontal lobe of his brain before exiting the top of his skull and landing approximately 80 feet away.

Amazingly, Gage not only survived the accident, he also went on to become one of the earliest and most famous cases in the then just emerging field of neurology.

A View of the Accident Site

This image depicts an area of railroad approximately three-quarters of a mile outside of Cavendish, Vermont. It was in this area where Gage was working for former Rutland & Burlington Railroad to prepare the railroad bed. It was in this area or a site nearby that Gage suffered from the accident that would change his life and make him famous in the annals of neurology.

News of Gage’s Accident

The above news clipping appeared in the Boston Post on September 21, 1848.

The article states:

“Horrible Accident – As Phineas P. Gage, a foreman on the railroad in Cavendish, was yesterday engaged in tamping for a blast, the powder exploded, carrying an instrument through his head an inch in length, which he was using at the time. The iron entered on the side of his face, shattering the upper jaw, and passing back of the left eye, and out at the top of the head.

The most singular circumstance connected with this melancholy affair is, that he was alive at two o’clock this afternoon, and in full possession of his reason, and free from pain.”

The piece contains a few inaccuracies, including suggesting that Gage’s jaw was shattered and understating the dimensions of the projectile. His attending doctor, John Martyn Harlow, kept notes on the case as it progressed, which he later published. While he described Gage as conscious and rational in the immediate aftermath of the accident, the man was certainly not “free from pain” as the above article suggested. In the days and weeks that followed, Gage would lapse into a state of delirium, followed by a semi-comatose state brought on by an infection.

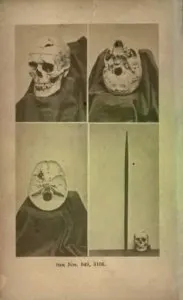

An Illustration of Gage’s Injury

This image depicts the path of the iron rod through Gage’s skull. The illustration was included in Dr. Harlow’s account of the accident and subsequent impact on Gage, which was first published in 1868 in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Medical Society.

“The missile entered by its pointed end, the left side of the face, immediately anterior to the angle of the lower jaw, and passing obliquely upwards, and obliquely backwards, emerged in the median line, at the back part of the frontal bone near the coronal suture,” Harlow wrote.

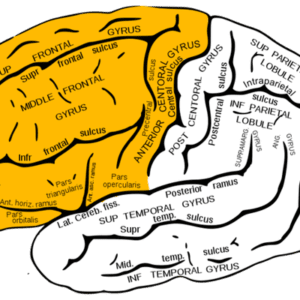

The Extent of Gage’s Brain Injury

Today, researchers have only Harlow’s description of the injury and examinations of Gage’s actual skull and the tamping rod to provide evidence of the type of injury that was sustained. Several different studies have been conducted to try to determine exactly how much of Gage’s brain was affected by the projectile. One 1994 study suggested that both prefrontal cortices were affected, while a 2004 study indicated that the damage was limited to the left frontal lobe. In 2012, a new study estimated that approximately 11-percent of Gage’s frontal lobe was destroyed and that 4-percent of his cerebral cortex was impacted.

While we will never be able to tell the exact extent of the damage, we do know that a significant portion of his frontal lobe was damaged.

The frontal lobe plays a vital role in problem-solving, decision-making, and planning. The area known as the prefrontal cortex is associated with the expression of personality. Other functions associated with the frontal lobe including reasoning, judgment, and impulse control.

In Harlow’s descriptions of Gage after the accident, he suggests that Gage would often make plans but fail to carry them out and that many of his friends described his personality as greatly changed, to the point that they felt he was “no longer Gage.”

Phineas Gage Life Mask

Prior to the 2009 and 2010 discovery of photographs of Phineas Gage, the only existing depiction that existed was a life mask made of his face and skull. The life mask was made for Henry Jacob Bigelow sometime around 1849 or 1850. Bigelow was a surgeon and professor at Harvard who published an article in American Journal of the Medical Sciences on Gage’s case, which helped generate considerable attention. Today, the life mask can be seen at the Warren Anatomical Museum at the Harvard University School of Medicine.

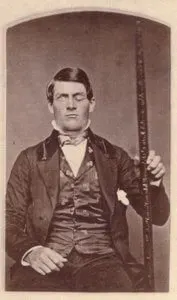

A Second Portrait of Phineas Gage

The second known photo of Phineas Gage came to light in 2010. The image was in the possession of members of Gage’s family. Like the previously seen portrait, Gage is shown proudly holding the tamping iron that so dramatically altered his life.

Gage’s Skull and the Famous Tamping Iron

Gage died in 1860 following a series of epileptic seizures, just 12 and a half years after his accident. In 1866, Harlow requested that the family exhume the body. The skull was removed and sent to Harlow, along with the iron tamping bar that had been in Gage’s possession at the time of his death. Today, both the skull and the iron rod can be seen at Harvard Medical School’s Warren Anatomical Museum.